Introduction

This is a personal, inside look at two grassroots international media campaigns. They took place during a time of political upheaval, on the frontline of a European war, of sorts: from 2011-2015 in Greece, during the country’s economic crisis.

This post serves as a practical example for the issues we discussed last week, on doing smart media relations. But it also includes thoughts on managing activist teams more generally. Like handling power struggles, dealing with political differences in the team, and transforming outrage into action. (See also: my best practices for building activist teams.)

It’s actually an edited transcript of an unpublished interview I did in March 2017, with the Media Activism Research Group. (I’ve removed the interviewer’s questions and added headings for clarity.) And it’s detailed, and rather long. But I think what this post puts forward is just as relevant for activist projects today, as it was in 2011 or 2017.

As always, if you have any feedback or thoughts on anything I’ve written here, get in touch!

OK, let’s go.

‘Lazy, angry Greeks’, and the occupation of the square

I’m British-Iranian, my wife is Greek, and in 2011 I moved to Greece to be with her.

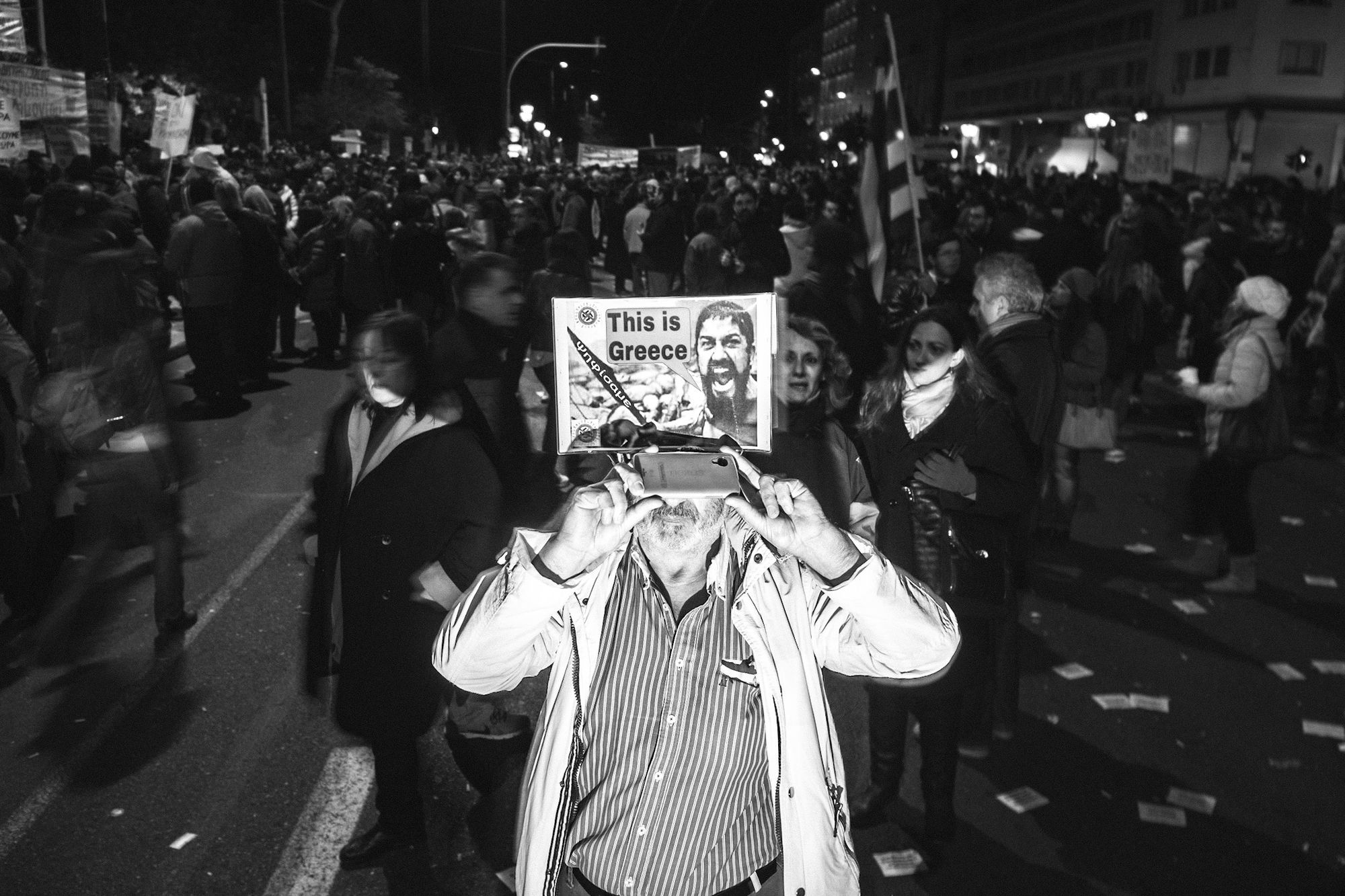

The Greek economic crisis had just exploded. The week I arrived in Athens, an occupation began of Syntagma Square, the political heart of the city. Thousands of people took the square and stayed there, in reaction to the brutal austerity measures that Greece’s EU lenders were forcing the country to accept.

I felt immediately that there was a problem with the international narrative about what was happening in Greece. Stereotypes of how Greek were lazy and corrupt were dominant in international media. And they were being used to make the case that Greece deserved what it was getting. Other points of view were not being equally represented.

I had some professional expertise in media relations and communications work. My assessment was that the imbalance in the Greek narrative was happening partly because of the way that news on Greece was being reported. Time-pressed journalists with little local knowledge were allowing the narrative to determine their sourcing — instead of the other way around.

On Twitter, for example, I'd often see journalists putting out calls like “looking for people who are out of work and Greek”, or “have you got a story of Greek corruption? Get in touch”. Or the journalists would speak to the usual local political commentators, who had adopted the line of the establishment they were part of.

The interviewee would then give the journalist the quote they wanted in the first place. Which inevitably carried the idea that Greeks had all been very naughty and were mad that they now were getting punished.

I even had the fortune to see with own eyes the machinery of this narrative being manufactured. At the start of the occupation in the Square, Canada’s CBC TV station approached a friend of mine. They asked him for a quote on what was happening, and pointed a camera at him. He described the situation eloquently, and against the backdrop of thousands of protesters, spoke about the resilience of the Greek people against the power of big capital.

Then the interviewer stopped and said to my friend:

“Excuse me, couldn’t you be a bit more angry?”

My friend said no; this was how he felt. And so CBC scrapped the interview and went off to find someone else, who presumably fit the profile they were looking for. A stereotypical angry Greek.

And I thought “Right, screw this, we have to do something”.

A first grassroots media relations project

So I got involved with a local citizen journalism outlet called Radio Bubble. They worked from a cafe in Athens' anarchist district. It was a hub for activists. With some people I met there, I organised an informal, pro-active media relations operation, which I called GreekSolutions.

The idea was simple. International journalists were flocking to Syntagma Square during the occupation. Our goal was to connect them to activists, that could provide the alternative view. It was traditional media relations work, as I had been doing for companies in London. Identify spokespeople, group them, segment them and offer interviews with these spokespeople to journalists.

And it worked quite well. It went on for a couple of months, and the group of spokespeople I’d gathered had interviews with outlets like BBC, CNN, and The Guardian. And we got some balanced coverage as a result.

But it came to an abrupt halt, one day in August. The authorities shut down the occupation — brutally. Riot police stormed the square with so much tear gas a cloud hung in the air for days. They destroyed equipment, computers, furniture, everything. The resistance lost the square, lost its focal point.

And so did we. That was the end of GreekSolutions.

Omikron Project: A creative campaign against damaging stereotypes

The dangerous stereotypes about Greek people, and the Establishment narrative, were still going around unchallenged. After spending a few months in a funk, I started a new project, in 2012.

I invited as many people as I could to a bar for a discussion about the international narrative on Greece, and the stereotype problem. I asked them to invite anyone they knew that might be interested.

Around 30 people showed up, most of whom had never met, and we sat there and had a great conversation. At the end, we said ‘OK, instead of talking about it, should we do something together?’. And everyone agreed and we arranged to meet again. The name of the bar was Omikron Bar so we called ourselves ‘Omikron Project’. And it grew into a creative media campaign.

As Omikron Project we made several productions: animated videos, ‘ads’ which were graphics underpinned by research, and a survey of grassroots groups in Greece. Our goal was to have a hook to hang a media pitch on, so we could try to change the narrative and show the other side of the country's story.

And between making those productions, we also did quite a lot of proactive media pitching. To get journalists to qualify their stories, or represent the alternative view. We chipped away at the Establishment narrative, bit by bit.

The most successful thing we did was our first Alex video. It went viral and had a quarter of a million hits on YouTube and got dubbed by ARTE and played on French and German TV.

The first episode of 'Alex, the lazy Greek' by Omikron Project

But more importantly, the video generated discussions and interviews and coverage. That coverage was the real output of Omikron Project.

Did we make an impact? A modest one, perhaps. Considering we worked on Omikron in our free time, between work and other commitments, without funds or support, I think we did OK.

Omikron worked well until 2015, when the left-wing Syriza government came in. Much of this activism got swallowed up into Syriza or stalled. For many people in Greece — erroneously I think — the enemy once again became obscure.

Collaborating in a polarised political environment

As Omikron Project we’d meet in the bar weekly, and advertise and open up the meeting each time to new people. Sometimes, 10 newcomers would show up. People came and went, but my sense was we had a cross-ideological sample of people; not all from the left. Which, I think, enriched the project.

The issue we could all agree on was this: Greeks were not being fairly represented internationally. Maybe our members couldn’t agree on the politics of it, or the details of that misrepresentation. But the overarching issue bound us together, and made it easier for us to collaborate.

The classic problem in Greece is that people can't work together because of political groupings, tribes. There are sociological and historical reasons for this. Left-on-left violence can be the most petty, bitter, angry thing you’ve ever seen. And in Greece it’s amped up to the next level.

Of course we had political disagreements in the group. But as I was coordinating it, I tried to keep the focus on the enemy: the damaging headlines, the Establishment generating them. We all knew how these stereotypes damaged people, and damaged Greece politically too.

Also, every time we had a win — a piece of coverage or even just a positive comment — we made sure everyone in the group knew about it. So people didn’t feel they were working on stuff and then sending it out into the ether. And that in turn motivated them to stay focused on the tasks, I think. Instead of having political squabbles.

The challenge of resources

We never had any issues with funding because we never wanted it, and fortunately we never needed it. We kept our ambitions low. A few times we were offered funds and we said no, because we didn’t want to create a split between who got paid and who didn’t. We didn’t want to be beholden to anyone.

Because there was no money, and no organisation behind the group, I think our audiences and potential new members had more in trust in us. Activists can be a very suspicious bunch, and sometimes with good reason.

Of course I recognise that we were all in a privileged position to be able to do Omikron Project at all. If people are working all day to try and feed themselves, they can’t volunteer like people who have those needs taken care of.

But in Greece there was — and I think there still is — an activist culture that I haven’t encountered in any other country. Greeks fit into their days the idea that they must do something politically, whatever that is. As I understand it, this culture pre-dated the economic crisis in Greece.

Also, we formed Omikron Project at a critical time in the country’s history. In 2011-2012, with the crisis in full swing, there was a lot of rage. In that environment, people make things happen. They’re angry and they know they have to do something. The environment provided its own momentum.

Transforming outrage into action

Outrage is raw energy. Activism aims to turn it into something productive; something that can have impact.

But too much outrage has diminishing returns. Meetings can turn into therapy sessions or back-to-back speeches, fast.

So it’s useful to have somebody on the team who is not as outraged as everyone else, who can act as a catalyst, who can see things dispassionately. Who can say “OK, maybe I don’t understand this specific issue as much as all of you. Maybe I’m not even as angry about it as you are, because it doesn’t affect me as it does you. But I’m angry enough to want to work with you and create something that can address it”.

I think in the case of Omikron, somehow I was able to play that role. I’m not Greek. The stereotypes of the lazy, corrupt, angry, rude Greek didn’t affect me directly. The outrage I felt wasn’t a fraction of what my Greek colleagues in Omikron probably felt. I think that dynamic was useful for the project.

Keeping the scope small

Having worked with NGOs, I knew the problem of trying to be too ambitious. In Omikron we kept the scope small. We only worked on one production at a time, and developed a process for it. Instead of scrambling to do everything in service of a massive vision of revolution that was probably not going to happen.

This is more of a business startup posture, but I think it’s a good way to be for any activist project. Because when that revolution doesn’t happen, it defeats you. And that’s what has happened across Greece, part of the reason activism in Greece stalled after 2015.

It helped that Omikron Project was concerned with something specific: the international narrative of Greeks. But we could have been much more strategic about it. We weren’t even like: ‘hey we’re gonna change that narrative’. Internally at least, it was more, ‘OK, let’s work on this production, which we think could help, and try to get some coverage on it. Then we'll see what happens’.

Less talking, more doing

We implemented those classic management mechanisms of making sure our meetings were organised and moderated. So they didn’t end up getting sidetracked into discussions and brainstorms. We had a lot of laughs, and we did talk a lot. But we always tried to end every meeting with a list of tasks, ownership and deadlines, which we followed up at the next meeting.

It helped that several key people in Omikron Project worked in marketing and advertising. So they had a professional, results-driven way of working that brought everyone else along with them.

Lots of activist groups get stuck in debates. It can be good therapy, sure. But if you’re all in a group to do something, to change something, all that matters is what leads to action.

Save Greek Water and its founder, Maria Kanellopoulou

There was a campaign here in Greece called Save Greek Water. They successfully opposed the privatisation of water in Thessaloniki, Greece’s second city. Maria Kanellopoulou who organised it, told me that she made it clear to anyone attending their meetings, “you’re here to work, not to talk”. And it sounded brutal, but Save Greek Water had an impact unlike many other groups. I’m sure that ‘action-first’ posture contributed a lot to it.

Decision making and democracy

Activist groups often paralyse themselves by making their processes as democratic and horizontal as they can be. By the idea that everyone, everyone in the group should have a say before the group can act.

On one hand, the broadest possible range of actors is vital to tap great ideas, enrich the process, and share the work. But you can’t aim for consensus on everything, have a vote about everything… because you’ll never move.

In Omikron Project we voted on things often. But part of the work of facilitation was ensuring we were only voting on the things that mattered. And that we were voting between concrete, distinct proposals that would set the direction.

Also, we always voted there and then — if people wanted to vote, they needed to attend the meeting. That made things move along much faster.

Power struggles in activist groups

Inevitably, many grassroots groups start with great intentions and then collapse. Often it’s for the same, simple reason: power. Who has it, who wants it, who didn’t get it when the group voted on it.

The same egos that exist in business, exist in activism. With the added complication that people are likely volunteering, so there’s no leverage. And they often won’t be familiar with the mechanisms of professional teamwork.

It’s terrible to see progressive groups fail because of power struggles. Because it’s so straightforward to learn basic facilitation techniques, and resolve these struggles before they can become a problem.

Fortunately Omikron Project didn't really suffer from this. There wasn't much 'power' to be had anyway. We just got on, and got on with the work. If people left, that was just the natural turnover of activist groups, and it was fine.

A brilliant Spanish activist once gave me advice on preventing squabbles and power struggles, that I still keep in mind:

Turn it down on each other; turn it up on our target.